When plunged into boiling water, the shell of a lobster turns bright red. That this glamorous transformation happens at the moment of being boiled alive seems to gesture cruelly to the potential telos of a lobster, as if it were their destiny to be eaten. Death becomes them, as it were. To a lobster that has been transformed thus, the culinary itinerary from pot to table might resemble a journey into the afterlife. The chef prepares and dresses their bright red corpse. He ceremoniously places slices of lemon around them, a jar of scented butter by their head. They are raised up in the air by white gloved hands, transported into a strange new world with low lighting and a gentle murmur of voices, then brought down to rest on a grand white table. A giant seated figure, napkin tucked under a round face, stares down at them, inspects them, and scoops up some of their flesh to taste it. It is Judgement Day.

Taste is a kind of judgment after all. It performs both an aesthetic and a moral function: the tongue asks the food how it tastes at the same time as wondering whether the food is poisonous. On the aesthetic level, taste is relational, it deals with the co-ordination between numerous compositional elements. The light flavour of a lobsters flesh is balanced by the thickness of the butter and the cutting tang of the lemon. Pleasure emerges from harmonic relationships produced in the mouth. The moral aspect of taste, however, deals in absolutes: is this poison/is this going to hurt me? Its purpose is to maintain a strict hierarchy between eater and eaten.

When you eat something you take its body into your body, absorb it and transform itself into yourself, but there is always the risk that the thing eaten could transform you from the inside. Food poisoning happens frequently with shellfish. Lobsters can accumulate saxitoxin in their liver and pancreas. After cooking, these organs resemble a greenish paste found in the shell of the lobster, known as tomalley. Saxitoxin causes temporary paralysis in humans: the toxin shuts down the nervous system. Most people are put off eating tomalley due to this risk, but to the decadent diner it is considered a delicacy.

In decadence, pleasure is weighed against disintegration. For all of its absolutist moral doctrines, there is a strong decadent undercurrent in Catholicism. While the Protestant vision of the body is mainly tied to its capacity for labour, Catholicism, with its oozing, liquid obsessions (the mortification and torture of its saints and martyrs, erotic unions with the divine, mystics breastfeeding from a lactating Christ, the desiccated relics of myroblyte saints leaking holy oil) flirts with the spiritual potential of flesh. Perhaps the most explicit example is the rite of communion, where wafers are transformed weekly into the body of Jesus Christ and consumed by the congregants. As they digest Jesus and absorb him into their body, Jesus, acting like a virus, begins to transform the congregants into God from inside of their stomach. This diagram of mutualistic digestion and relational transformation feels both sensuous and positively pagan. Under the moralistic surface lies an obsession with terminal ecstasy, an orgasmic extinction of self.

– Justin Fitzpatrick

Justin Fitzpatrick, A Conflict of Interests, 2020

Oil on linen

92.6 x 73 cm

Justin Fitzpatrick, Chef’s Table: France, 2020

Oil on linen

92 x 183 cm

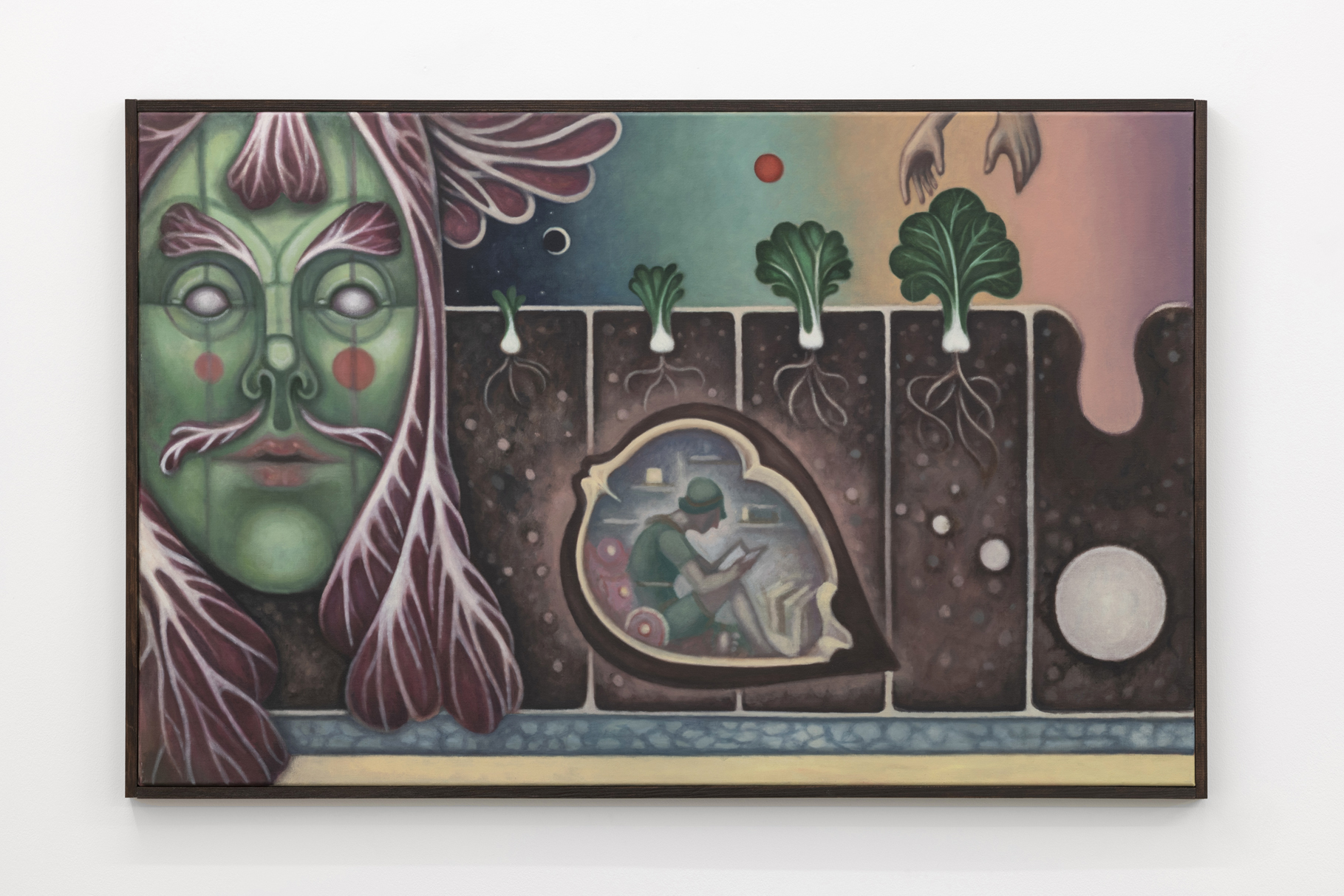

Justin Fitzpatrick, Alpha Salad: The Demiurge and the Seed, 2020

Oil on linen

112.8 x 72.8 cm

Justin Fitzpatrick, Bathing (After Duncan Grant), 2020

Oil on linen

72.5 x 52.9 cm

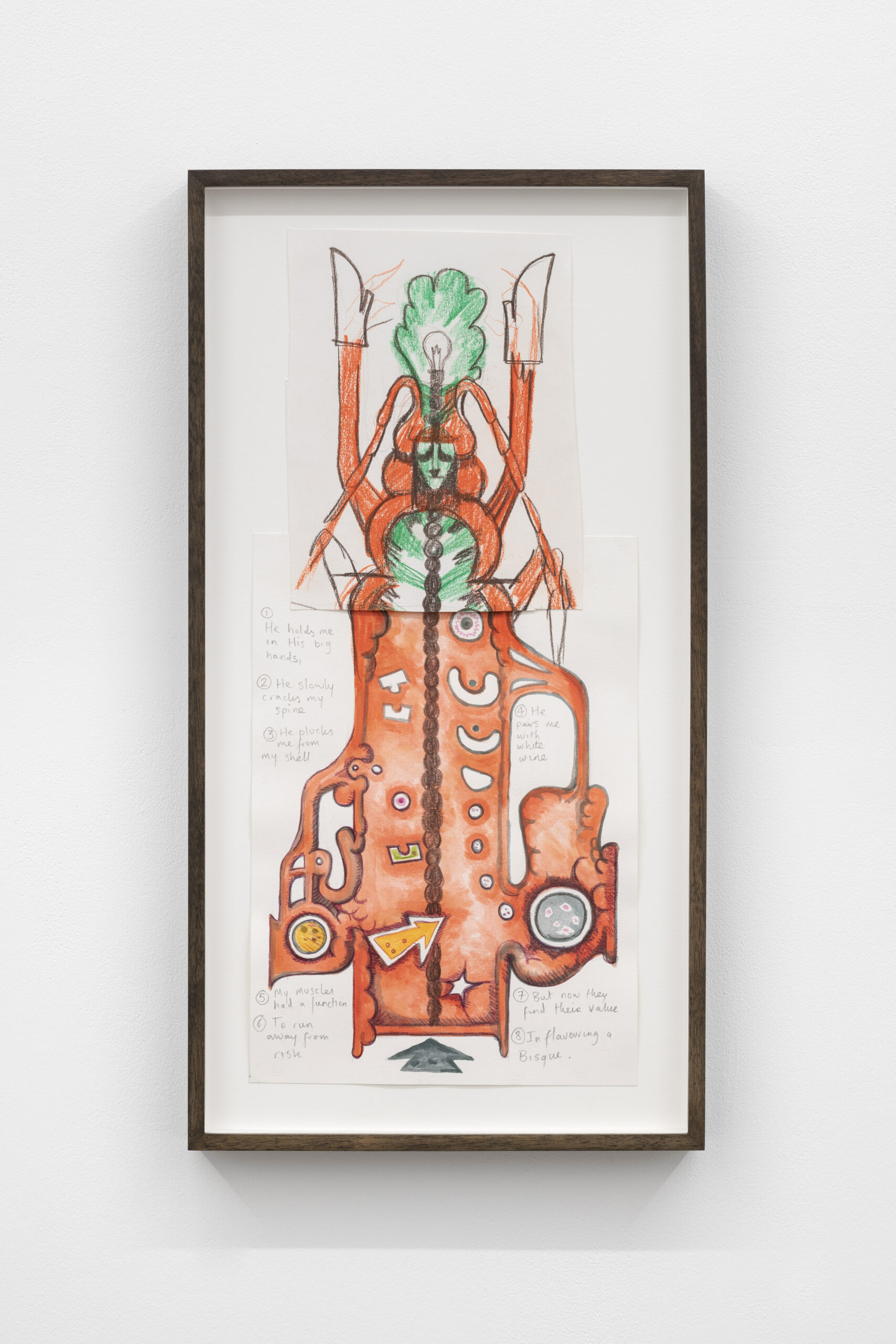

Justin Fitzpatrick, Bisque, 2020

Watercolour and coloured pencil on paper

56.5 x 30 cm

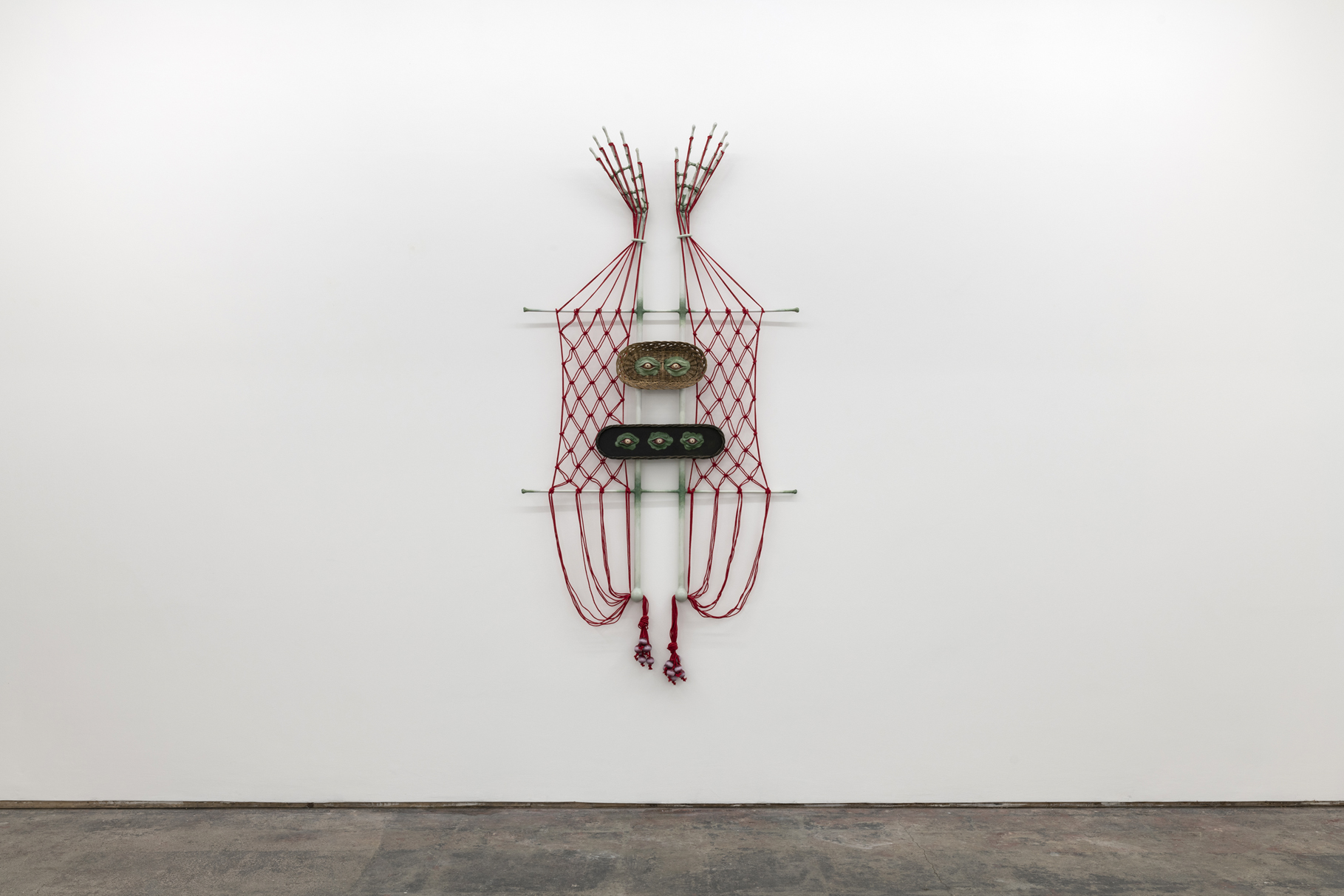

Justin Fitzpatrick, Flexor Bread-basket, 2020

Wood, epoxy clay, wire, cotton rope, acrylic paint and woven basket

207 x 101 x 18 cm

Justin Fitzpatrick, Cuisine Roulante, 2020

Coloured pencil on paper

30 x 39.5 cm

Justin Fitzpatrick, Filet du Cheval au Citron, 2020

Justin Fitzpatrick, Filet du Cheval au Citron, 2020Oil on linen

142 x 113 cm

Justin Fitzpatrick, Lemon Entry, 2020

Oil on linen

92.6 x 52.6 cm

Justin Fitzpatrick, Omega Salad, 2020

Oil on linen

70 x 110 cm

Justin Fitzpatrick, Psychopomp, 2020

Oil on linen

183 x 142.5 cm

Justin Fitzpatrick, The Decadent, 2020

Wood, epoxy clay, wire, cotton rope, acrylic paint, synthetic hair and synthetic leather

160 x 158 x 33.7 cm

Justin Fitzpatrick, The Garden Salad of Forking Paths, 2020

Oil on linen

182.5 x 52.9 cm